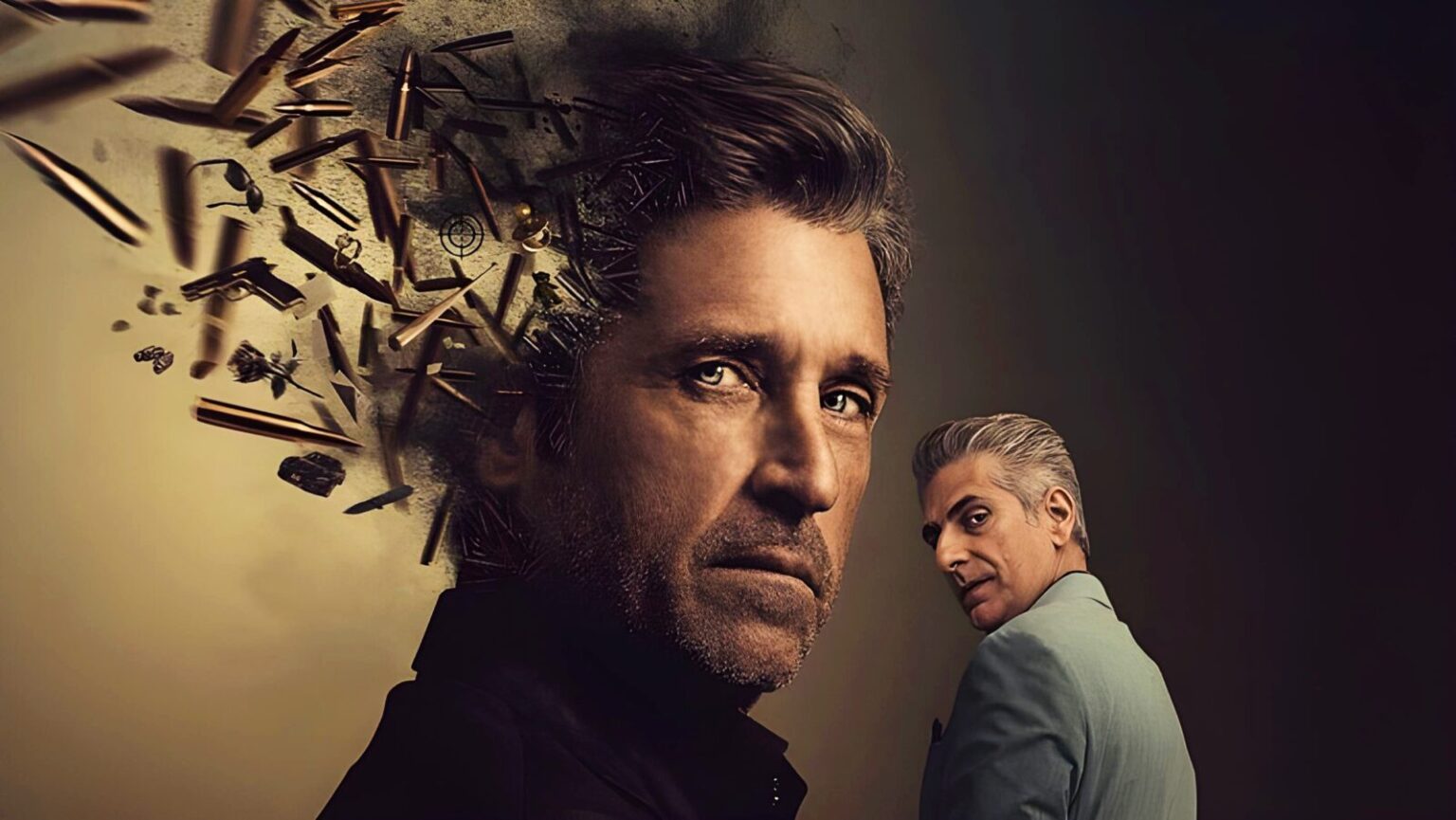

TL;DR: Memory of a Killer takes the well-worn hitman thriller and injects it with real psychological horror by trapping us inside the failing mind of its protagonist. Patrick Dempsey delivers a surprisingly restrained and gripping performance, Michael Imperioli steals scenes with effortless authority, and the show’s willingness to embrace confusion as a storytelling tool makes it one of the most memorable action thrillers in recent years.

Memory of a Killer

There’s a moment early in Memory of a Killer where I realized this show wasn’t playing the same old assassin hits playlist we’ve all heard on shuffle for the last decade. Patrick Dempsey’s Angelo pauses in the middle of his perfectly calibrated routine, looks genuinely unsettled, and asks himself a question no hitman ever wants to ask: what was I just doing? That pause, that microscopic crack in the armor, is where this series lives. And once you’re in that headspace, it never lets you out.

I’ve watched more hitman stories than I care to admit. I’ve sat through balletic gun-fu, morally conflicted contract killers, retired legends dragged back in for one last job. I love the genre, but I’m also exhausted by it. The trick in 2026 isn’t slicker action or louder violence, it’s perspective. Memory of a Killer understands that, then weaponizes it by anchoring the entire experience to a man whose own mind is slowly betraying him. The result is a thriller that doesn’t just want you tense, it wants you uneasy, second-guessing every cut, every missing beat, every unexplained injury.

At the center of it all is Dempsey, delivering what is easily one of the most controlled and quietly terrifying performances of his career. If you still associate him primarily with charming doctors and rom-com charisma, this show feels like watching Clark Kent reveal he’s been Batman the whole time.

Memory of a Killer follows Angelo, a veteran contract killer whose professional life is defined by precision, discipline, and ritual. His personal life, meanwhile, is aggressively mundane. He’s a father. A soon-to-be grandfather. A man who sells photocopiers for a living, at least as far as his pregnant daughter Maria is concerned. This split existence is familiar territory for the genre, but the show’s execution is anything but routine. The series uses environments as psychological shorthand, and it’s shockingly effective. Suburban calm, soft lighting, sensible clothes, small talk. Then a transition ritual straight out of a modern noir fever dream: an abandoned garage, clothes discarded like a shed skin, a sleek black suit, a Porsche growling toward New York City as skyscrapers loom like judgment.

What impressed me immediately is how patient the show is with these transitions. It doesn’t rush you from dad mode to assassin mode. It lingers. It lets the tension build in the quiet moments, because it knows the real threat isn’t the next target, it’s the gaps forming in Angelo’s memory. And once those gaps start appearing, the entire narrative structure bends around them.

The Alzheimer’s angle isn’t a gimmick here. It’s the engine. Small slips come first: a forgotten code, a misplaced bag, a jacket left behind in the wrong house. The show’s editing pulls you directly into Angelo’s deteriorating perception. We don’t always see what he forgets, we experience the absence of it. Scenes end without closure. Actions happen off-screen. Consequences appear without context. When another character points out something Angelo doesn’t remember doing, you feel the same cold drop in your stomach that he does.

There are moments where this approach flirts with disorientation, and I’ll be honest, I wrestled with it. A sniper rifle appearing already assembled. A fresh wound noticed by a doctor that we never saw inflicted. In a lesser show, these would feel like continuity errors. Here, they sit in that uncomfortable gray area where you’re never quite sure if the show is being clever or sloppy. What ultimately sold me is that the confusion serves the theme. Even when it’s imperfect, it reinforces the central horror: this is a man losing his grip on reality in a profession where missing a single step gets you killed.

The paranoia isn’t confined to Angelo’s professional life either. His personal world starts bleeding into the danger zone in ways that feel both inevitable and cruel. His daughter Maria isn’t just emotional collateral, she’s the emotional core of the series. Their relationship grounds the show, and every scene between them carries an undercurrent of dread. You’re constantly waiting for the moment when the truth spills out, when the lies collapse, when his past comes crashing into her life with irreversible force.

That collision accelerates once old sins come knocking. A past assassination, a release from prison, a retaliatory strike that lands far too close to home. The show smartly avoids turning this into a simple revenge plot. Instead, it becomes a pressure cooker. Multiple threats, overlapping timelines, and a protagonist who can’t trust his own memory to keep them straight. The tension isn’t just about who’s coming for Angelo, it’s about whether Angelo can even remember why.

If Dempsey is the anchor, Michael Imperioli is the accelerant. His performance as Dutch, Angelo’s handler and longtime friend, is an absolute masterclass in controlled menace and charm. Fans of The Sopranos will immediately recognize the energy he brings, but this isn’t Christopher Moltisanti redux. Dutch is subtler, older, more calculating. A man who smiles easily while constantly running cost-benefit analyses in his head.

The chemistry between Dempsey and Imperioli is the beating heart of the series. Every scene they share crackles with history. There’s an ease to their interactions that sells decades of shared bloodshed and loyalty. When they laugh together, it feels earned. When they disagree, it feels catastrophic. The show understands that emotional stakes matter more than body counts, and nowhere is that clearer than in the way it frames the potential fracture of this relationship as more dangerous than any gunfight.

One scene in particular, centered around a spoiled surprise party and a hilariously awkward exchange of “surprise faces,” shouldn’t work on paper. In execution, it’s brilliant. It humanizes both men without undercutting the threat they represent. It also makes the eventual tension between them hurt in a way no shootout ever could.

From a technical standpoint, Memory of a Killer is sharp without being flashy. The action is grounded and often messy. Fights don’t feel choreographed so much as survived. Angelo wins not because he’s invincible, but because he’s experienced, ruthless, and just competent enough to adapt on the fly. The cinematography favors clarity over spectacle, and when it does get stylized, it’s always in service of Angelo’s fractured perspective.

What I appreciated most is that the show trusts its audience. It doesn’t over-explain the disease. It doesn’t spoon-feed motivations. It lets silence do a lot of the work. In an era where many thrillers are terrified of viewers missing a plot point, this one is confident enough to let you sit in uncertainty. That confidence goes a long way.

By the time the season reaches its later episodes, the tension has evolved into something heavier. It’s no longer just about survival, it’s about identity. Who is Angelo when the memories that define him start slipping away? Is he the monster he’s been pretending not to be, or the father he desperately wants to remain? The show never offers easy answers, and that’s to its credit.

Memory of a Killer isn’t reinventing the assassin genre from scratch, but it doesn’t need to. What it does is take familiar pieces and rewire them around a genuinely unsettling concept, then commit to that concept even when it gets uncomfortable. Anchored by a career-best performance from Patrick Dempsey and a magnetic turn from Michael Imperioli, it’s a thriller that stays with you long after the credits roll, not because of what you saw, but because of what you didn’t.