TL;DR: Netflix’s Dept. Q is a masterfully brooding crime drama that trades in Nordic noir for Scotland’s damp, gothic soul. Matthew Goode delivers a career-defining performance as Carl Morck, a self-loathing detective banished to the bureaucratic abyss of cold-case purgatory. Haunting, elegant, and wickedly sharp, Dept. Q is as much about guilt and emotional ruin as it is about solving crimes. It’s slow-burn brilliance that earns every minute of its runtime.

Dept. Q

The Basement Chronicles: A Descent into Dept. Q

When we talk about prestige TV, the conversation tends to circle around grandiosity—sweeping cinematography, orchestral scores, ensemble casts that drip with Emmys before a word is even spoken. But every once in a while, a show sidles into the room like a cold draft through an old stone wall—quiet, chilling, and impossible to ignore. Dept. Q is that draft. And I mean that in the best way.

Created by Scott Frank (The Queen’s Gambit) and based on Jussi Adler-Olsen’s beloved Danish novels, Dept. Q takes a Scandinavian crime franchise and filters it through a distinctly Scottish lens. The result is a rain-slicked, cigarette-burned gem of a series that simmers with tension and refuses to coddle its viewers. It dares you to look away—and good luck with that.

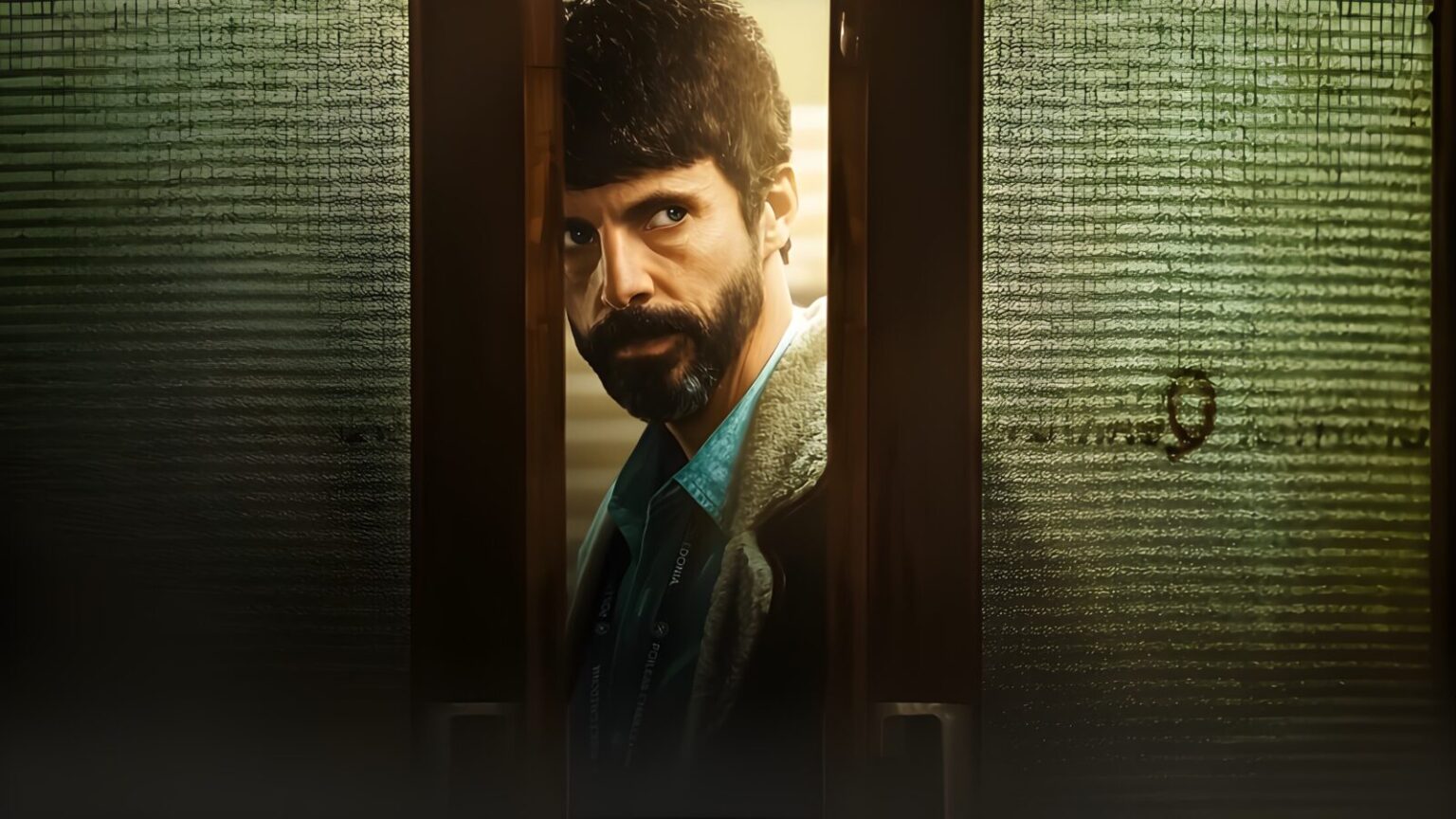

Our anti-hero, Carl Morck, played with a kind of unwashed elegance by Matthew Goode, is a man who seems built from regret and cigarette ash. He’s the kind of detective you get when you subtract heroism from talent and then multiply the whole thing by a bruised ego. After a catastrophic raid leaves one officer dead, another paralyzed, and Morck bleeding from the neck (literally and metaphorically), he’s exiled to the Edinburgh police department’s version of Siberia: the basement. There, in the lowly dungeons of bureaucracy, he’s tasked with heading up the newly minted Department Q, investigating cold cases with zero resources and even less support.

Cue the archetypal misfit crew: a young cadet recovering from a mental health crisis, a paralyzed former partner offering advice from a hospital bed, and a Syrian refugee with a badge in exile. They sound like the setup for a joke, but they are the emotional core of this elegiac, labyrinthine series. Their first case? The disappearance of Merritt Linguard, a young lawyer whose story is soaked in enough dread and sorrow to make even the most jaded true crime aficionado squirm.

Trauma as Architecture

What Dept. Q does so well—and so quietly—is frame emotional trauma as both character arc and visual motif. Every hallway is narrow. Every light flickers. The camera lingers on the peeling paint and mold spots in the basement HQ like it’s trying to give the building PTSD. Edinburgh, all gothic spires and damp stone, becomes a character in itself, an accomplice to the crimes that haunt its corners.

Scott Frank’s direction is deliberate, even meditative. He allows the story to breathe, sometimes wheezing through grief, sometimes gasping at revelation. This isn’t a procedural for the Law & Order crowd. The crimes are complex, messy, often uncomfortably personal. And every resolution feels like it comes at a cost. Morck’s victories don’t inspire fist pumps—they elicit sighs, shudders, and the occasional gulp of whisky.

Performance as Catharsis

Matthew Goode’s turn as Morck is the show’s emotional load-bearing beam. Gone is the charming gentleman of Downton Abbey or the slick Lord Snowdon of The Crown. Here, Goode is gaunt, bearded, and hollow-eyed, like he crawled out of a Faulkner novel and landed in a police procedural. His Morck is not likable, not even a little. But he’s magnetic—bristling with sarcasm, contempt, and a deep, silent terror of his own irrelevance.

Kelly Macdonald, who plays Morck’s assigned therapist, deserves her own spinoff. Her scenes are less therapy and more excavation. You watch her gently pick away at the jagged edges of Morck’s psyche, and it’s like watching someone try to defuse a bomb using only empathy and a clipboard.

The supporting cast is equally stellar, particularly Alexej Manvelov as Akram, the exiled Syrian cop who picks the first cold case. His performance anchors the show in a moral center that Morck can’t (or won’t) inhabit. Leah Byrne brings a subtle grace to Rose, the cadet whose own trauma simmers just beneath the surface.

A Study in Suffering

The cases themselves are bleak, but they never feel exploitative. The disappearance of Linguard unfolds in brutal, meticulous flashbacks. The show flirts with voyeurism but pulls back just enough to let our imaginations do the worst. There’s violence, yes, but it’s the emotional violence—the betrayals, the guilt, the shame—that really cuts deep.

By episode four, I stopped thinking of Dept. Q as a crime drama and started thinking of it as an extended meditation on grief. Every character is broken in some unique, exquisitely personal way. And instead of trying to fix each other, they learn to function within the fracture. This is what makes the series feel so intimate, even as it sprawls across Scotland’s hills and alleys.

Final Thoughts: The Beauty of the Basement

There’s a version of Dept. Q that could’ve been a rote, trope-filled detective drama. But Scott Frank’s adaptation insists on more. It asks questions about justice and closure, about guilt and redemption. It gives us a hero who doesn’t want saving, and crimes that won’t stay solved. It’s a show about basements—both literal and metaphorical—and what we bury there.

In the age of prestige TV fatigue, where even excellent series begin to blur into one another, Dept. Q stands out. It’s patient, poetic, and laced with a distinctly Scottish melancholy. Watch it with the lights low, your expectations recalibrated, and maybe a drink in hand.

Final Verdict: Dept. Q is a grim, lyrical powerhouse of a series that eschews genre clichés in favor of character, craft, and unrelenting mood. If you’re willing to descend into its shadows, it’ll reward you with something rare: a crime story that actually feels like a wound healing in real time.