Before group chats muted themselves into irrelevance and read receipts sparked passive-aggressive debates, instant messaging was a full-blown event. You didn’t just send a message — you logged in. You curated your status. You chose the perfect display name with just the right mix of sarcasm and song lyrics. And if someone signed off dramatically, you noticed.

Among the many platforms that defined the early internet, three stand above the rest for their cultural impact and feature creep brilliance: AOL Instant Messenger, MSN Messenger, and BlackBerry Messenger, and ICQ. Each helped build the blueprint for the messaging apps we now treat as utilities.

AOL Instant Messenger, or AIM, launched in 1997 and quickly became the social backbone of the dial-up era. Logging into AIM felt ceremonial. The door-creak sound effect when a friend signed on was practically Pavlovian. Your buddy list wasn’t just a contact roster — it was a real-time map of your social universe. Who was online? Who was ignoring you? Who set an away message that was clearly aimed at someone specific?

The away message itself deserves academic study. It was part diary, part subtweet, part existential poetry. Song lyrics, cryptic one-liners, dramatic declarations like “don’t text me” before texting existed — AIM users turned 200 characters into performance art. Technically, AIM also normalized features we now expect: file transfers, group chats, user profiles, and customizable screen names that somehow always included extra vowels or random capitalization. Though it officially shut down in 2017, its influence had already seeped into every modern messaging interface.

Then came MSN Messenger in 1999, Microsoft’s answer to the instant messaging boom. If AIM was your social diary, MSN Messenger was your chaotic best friend. It introduced features that felt almost mischievous. The “nudge” button didn’t just notify someone — it shook their entire chat window like a digital earthquake. You could not ignore a nudge. You could only retaliate.

MSN also embraced early webcam support and voice chat, pushing beyond text before broadband was widespread. Animated “winks” and expressive emojis made conversations louder, brighter, and slightly unhinged in the best way. By the mid-2000s, MSN Messenger had become a nightly ritual for millions of Windows users. It eventually gave way to Skype as Microsoft consolidated its communication strategy, but its playful DNA can still be seen in modern reaction features and attention-grabbing notifications.

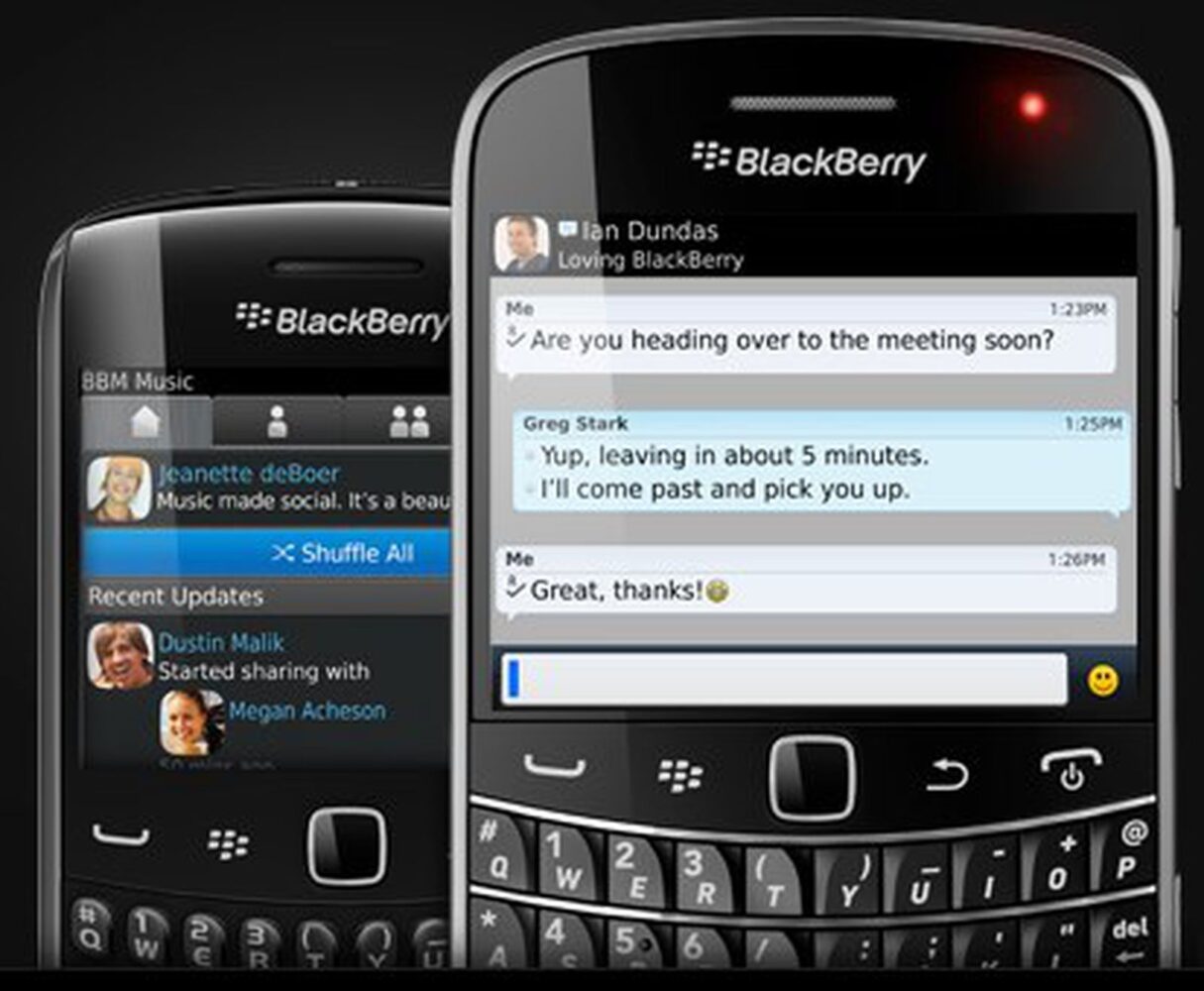

If AIM and MSN ruled the desktop, BlackBerry Messenger — BBM — owned the early smartphone era. Launched in 2005, BBM felt futuristic. While everyone else was counting SMS messages like they were precious gems, BBM ran over the internet. Messages were fast. Delivery receipts were instant. And those tiny “D” and “R” indicators (Delivered and Read) changed social dynamics forever. Suddenly, you knew when someone had seen your message. And they knew that you knew.

BBM’s PIN system added a layer of mystique. You didn’t just hand out a phone number — you shared a unique identifier tied to your device. Combined with BlackBerry’s physical keyboards, BBM made rapid-fire messaging efficient in a way that felt almost professional. For a stretch of time, especially among students and business users, BBM wasn’t optional. It was the default.

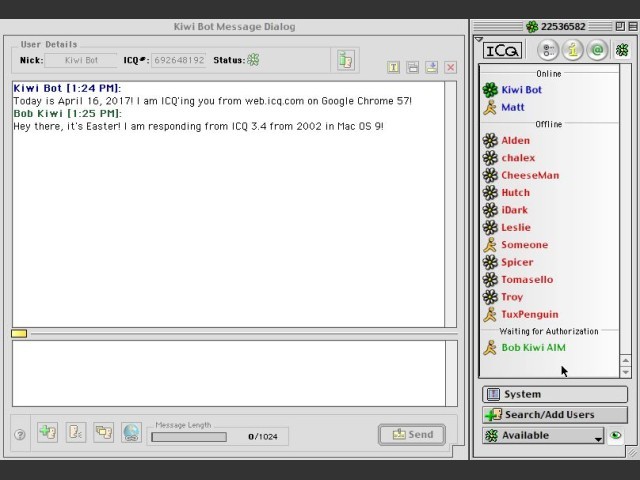

And then there was ICQ, the often-overlooked pioneer that launched in 1996, even before AIM. Its name was a phonetic play on “I seek you,” and its signature “uh-oh!” notification sound became one of the earliest audio cues of internet connectivity. ICQ introduced universal identification numbers (UINs), long strings of digits that users memorized like secret codes. It supported offline messaging, file transfers, and searchable user directories at a time when the web itself still felt experimental. Though it eventually faded as competitors streamlined the experience, ICQ laid much of the technical groundwork for everything that followed.

What makes AIM, MSN Messenger, BBM, and ICQ endure in memory isn’t just nostalgia. They established the social grammar of digital communication. Online presence became measurable. Response time gained emotional weight. Status updates became subtle storytelling tools. The expectation of immediacy — that someone, somewhere, was reachable in real time — became normalized.

Today’s messaging apps are sleeker, encrypted, and consolidated into mobile ecosystems. But strip away the polish, and the fundamentals remain remarkably familiar. The sounds may be gone, the buddy lists replaced by algorithmic feeds, yet the core experience — waiting for someone to reply, curating how you appear online, interpreting a read receipt — was perfected decades ago.