TL;DR: Netflix’s Splinter Cell: Deathwatch looks the part but forgets the soul. It’s another casualty of the Halo Curse—slick, noisy, and empty where it should’ve been quiet, deliberate, and human.

Splinter Cell: Deathwatch

There’s a particular kind of silence that only a Splinter Cell fan knows. It’s that tense, glowing-green hush when you’re crouched in the dark, heart hammering, watching a guard pass inches away from your knife. It’s the sound of control, of precision, of patience rewarded and chaos punished. It’s a rhythm—one that defined the series, one that made Sam Fisher more of a ghost than a soldier. And when Netflix announced Splinter Cell: Deathwatch, that rhythm was the only thing I prayed they wouldn’t ruin.

Spoiler: they did.

What Netflix and Ubisoft have delivered instead is another entry in the modern catalogue of almosts—a show that almost gets it, almost honors its source, almost gives fans a reason to believe that the dark age of half-baked game adaptations is over. But Deathwatch is haunted by something worse than mediocrity. It’s haunted by the Halo Curse.

You know the one. The curse that strikes when an adaptation takes a property defined by immersion, silence, and personal agency, and sandblasts it into a noisy, indistinguishable content product with no soul. Halo on Paramount+, Resident Evilon Netflix, Cowboy Bebop on Netflix again (seriously, how many times must we teach you this lesson, old man?). Deathwatch joins their ranks with depressing ease.

The Ghost of Sam Fisher

When I booted up Splinter Cell: Deathwatch, I wanted to believe. I really did. Derek Kolstad, the creator of John Wick, was at the helm—a man who knows how to turn action into language, how to tell stories with motion and violence and style. On paper, this should have been a slam dunk: Kolstad’s brutal precision mixed with Ubisoft’s richest lore. Instead, what we get is a show that treats Sam Fisher like a franchise logo with a pulse.

Our Sam (voiced by Liev Schreiber, whose gravelly authority does its best to fill the Ironside-shaped void) is old, tired, and living in some vague, post-mission limbo when a wounded agent—Zinnia McKenna, voiced with more effort than the script deserves—shows up on his doorstep. The setup reeks of a thousand other spy thrillers. A retired operative pulled back in. A mission gone wrong. A conspiracy reaching to the top. You could swap Fisher for Bourne, Bond, or Bauer and barely have to rewrite a line.

That’s the core sin of Deathwatch: it forgets why Splinter Cell mattered. The franchise wasn’t about plot twists or explosions; it was about restraint. Every level felt like a puzzle box that dared you to think instead of shoot. Fisher wasn’t cool because he killed people; he was cool because he didn’t have to. He was the calm center of chaos, the embodiment of the phrase “one man army” whispered instead of shouted.

In Deathwatch, he’s just another grizzled old killer.

A Franchise Declassified

Let’s talk about what Netflix actually got right: the first ten minutes. The opening sequence of Deathwatch is pure Splinter Cell energy—a silent infiltration, green lenses cutting through the dark, sound design so crisp you could almost feel your controller vibrating. For a moment, I thought we were in good hands. Then the show starts talking. And it never shuts up again.

Every espionage trope gets rolled out like a greatest hits album of mediocrity: the bureaucratic boss, the cocky rookie, the world-ending MacGuffin. You can feel the writers checking boxes instead of building tension. And Kolstad’s trademark precision? Nowhere to be found. It’s as if someone took John Wick, stripped it of its rhythm, and left only the gunfire.

Animation-wise, Deathwatch is fine. That’s it—fine. The character models are serviceable, the action sequences decently choreographed, and the lighting occasionally flirtatious with brilliance. But it’s all undercut by direction that feels allergic to silence. The visual storytelling that made Arcane and Castlevania sing is missing here; every quiet moment gets filled with exposition or moral handwringing.

Even worse, the show has no idea what to do with its own mythology. It leans on Splinter Cell’s iconography—the night vision goggles, the Third Echelon emblem, the whispery comms chatter—but it never explores the actual ethics or psychology of stealth. The games were obsessed with the idea of surveillance, of state control, of what it means to live unseen in a world that’s always watching. Deathwatch nods to those ideas like a student bluffing through an oral exam.

The Halo Curse

There’s something almost poetic about the way Deathwatch joins Halo and Resident Evil in adaptation purgatory. All three share the same problem: they mistake aesthetics for identity. They think that by slapping familiar names and gadgets onto a generic story, they’ve captured the magic. But aesthetics without philosophy are cosplay. And Splinter Cell, more than most, is built on philosophy.

When Halo turned Master Chief into a guy who takes his helmet off to cry about his feelings, fans didn’t riot because he was emotional; they rioted because the show mistook mystique for emptiness. Chief’s silence was narrative gravity—it pulled you in, made you project. Sam Fisher is the same. We never needed to know what brand of whiskey he drinks or how often he calls his daughter. We needed to believe that when the lights go out, he’s still out there, patient, efficient, inevitable.

Deathwatch tries to humanize him in all the wrong ways. It drags him through clichés, gives him exposition where menace should be, and turns his calculated lethality into generic badassery. Fisher has always been a ghost; here, he’s a man holding a flashlight, hoping we’ll mistake the glare for depth.

The Curse of Adaptation Fatigue

We’re living through the golden age of video game adaptations—or so we keep being told. The Last of Us shattered expectations. Arcane redefined animation. Cyberpunk: Edgerunners made a broken game feel alive again. But each success only sharpens the sting when something like Deathwatch drops the ball.

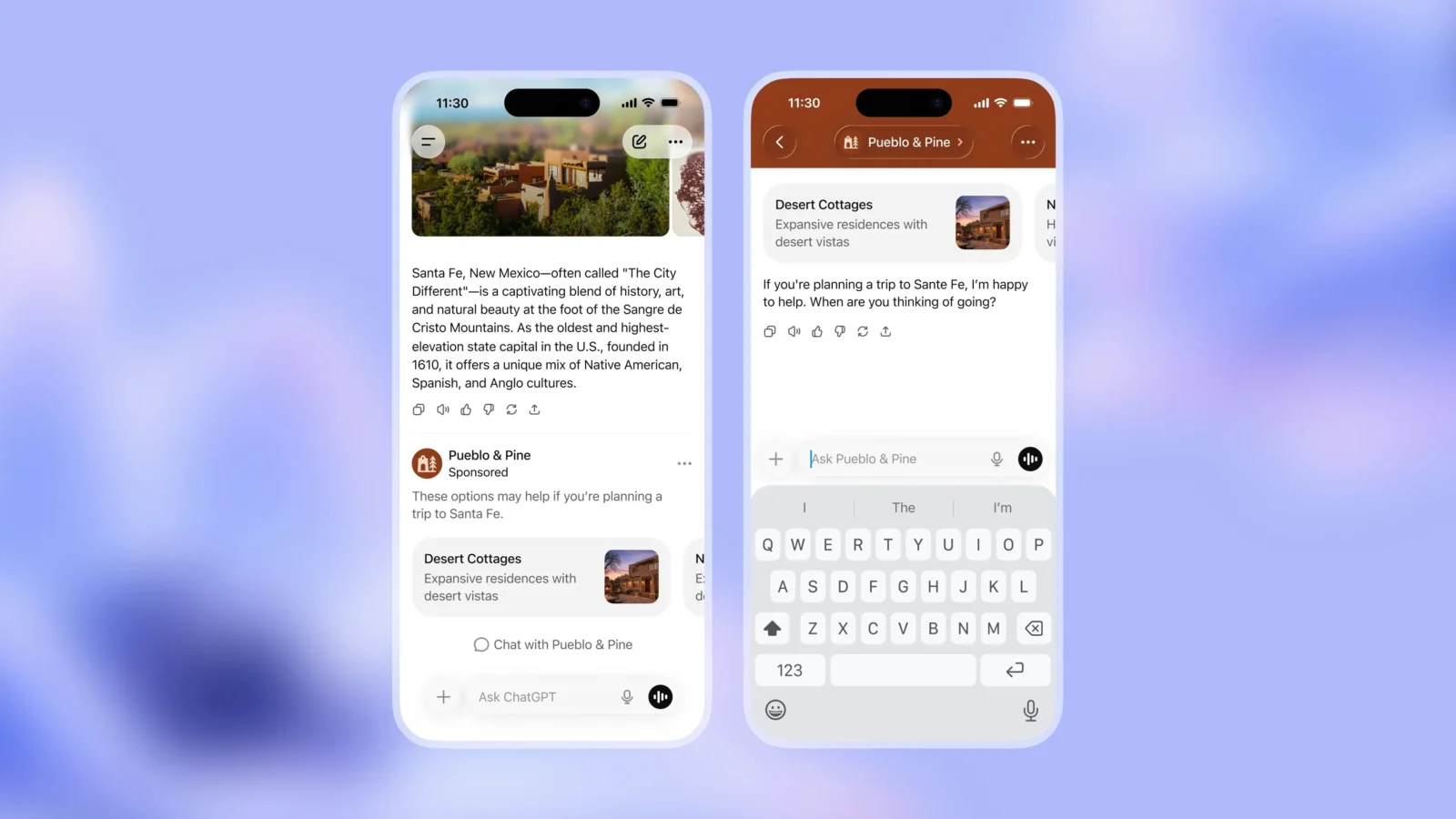

Netflix, in particular, has developed a nasty habit of treating IPs like ingredients in a content smoothie. Blend one part brand recognition with two parts action template, sprinkle in a famous voice actor, and boom—you’ve got something to fill the algorithm’s bottomless pit. But games like Splinter Cell don’t survive that treatment. They require intimacy. They require a kind of cinematic humility that trusts the quiet to carry weight.

Instead, Deathwatch mistakes motion for meaning. Every time the plot threatens to pause long enough to build tension, another explosion interrupts it. Every time Fisher could demonstrate brilliance through silence, he delivers a line that feels ripped from a rejected Call of Duty cutscene. It’s exhausting—not because it’s bad television, but because it’s lazy television wearing a legend’s face.

A Tale of Two Voices

Let’s talk about Liev Schreiber. The man’s voice is practically weaponized gravel, and he does what he can with a script that confuses gravitas for grit. He channels just enough Ironside to make you remember what’s missing. And that’s the problem. His performance doesn’t fail because he’s wrong for the role; it fails because the show never lets him be Sam Fisher. You can hear the restraint in his delivery, the ghost of what this could’ve been if Netflix had called Michael Ironside instead.

Fans will tell you Ironside is Fisher—not just because of nostalgia, but because his voice carried moral weight. Every word sounded like it had been sanded down by decades of moral compromise. Ironside’s Fisher wasn’t just gruff; he was weary. Haunted. Dangerous. Schreiber’s Fisher sounds like he’s waiting for the director to let him act.

And then there’s the supporting cast, who exist mostly to remind you that you’re watching a TV show. There’s the overconfident rookie, the bureaucratic superior, the hacker with a heart of gold—it’s like someone dumped a CIA drama template into ChatGPT and hit “generate.” No one feels real, no one feels dangerous, and no one challenges Fisher in a way that reveals character. They’re not people; they’re obstacles in a screenplay.

The Tragedy of Stealth in Modern Media

Here’s the thing about stealth: it’s cinematic by nature. The interplay of shadow and light, silence and sound—it’s pure visual storytelling. Hitchcock knew it. Fincher knows it. The Splinter Cell games were built on that principle. They trusted the player to feel suspense rather than be told about it.

So why do so many adaptations get it wrong? Because television has forgotten how to be quiet. We’ve traded tension for tempo, subtext for spectacle. Deathwatch could’ve been a masterclass in minimalist suspense—a spiritual successor to Ghost in the Shell with Tom Clancy’s fingerprints. Instead, it feels like someone tried to turn Metal Gear Solid into a Fast & Furious spin-off.

Watching in the Dark

About halfway through the series, there’s a scene that perfectly encapsulates everything wrong with Deathwatch. Fisher infiltrates a heavily guarded compound—a classic Splinter Cell setup. The animation builds it up beautifully: tight corridors, shifting camera angles, a palpable hum of danger. For thirty seconds, you think, yes, this is it, this is Splinter Cell. Then the lights flicker on, a dozen guards burst in, and we’re back to loud, generic gunfights. The stealth dies so the pacing can live.

It’s the creative equivalent of turning on night vision goggles in broad daylight.

Ubisoft’s Vanishing Act

I can’t blame Kolstad alone for this mess. Ubisoft has been fumbling Fisher’s legacy for over a decade. Blacklist came out in 2013, and since then, the company’s been too busy turning Assassin’s Creed into a content farm to remember the series that taught gamers how to disappear. Deathwatch feels like the final nail in that coffin—a corporate shrug disguised as fan service.

Ubisoft’s collaboration with Netflix should’ve been a chance to redeem themselves. Instead, it feels like they licensed out a legend and forgot to check the dailies. When you compare it to the passion and precision of something like Arcane—which practically oozes love for its source—you start to realize how hollow this project is. Deathwatch wasn’t made forfans; it was made from fandom, mined like a resource.

Final Approach

By the time the credits rolled, I didn’t feel angry. I felt tired. Tired of watching studios mistake noise for narrative. Tired of watching talented creators play it safe. Tired of watching one of gaming’s greatest icons reduced to a symbol on a Netflix thumbnail.

Splinter Cell: Deathwatch isn’t unwatchable. It’s competently animated, occasionally stylish, and mercifully short. But competence isn’t enough when you’re dealing with a property this iconic. Fisher deserved better. We all did.

Because here’s the cruel irony: stealth games are about trust. The player trusts the system to reward patience, precision, and thoughtfulness. We trust that if we stay in the shadows, the game will let us thrive there. But when it comes to Hollywood and Netflix? That trust is long gone.